JWT attacks - Web Security Academy

本文由 简悦 SimpRead 转码, 原文地址 portswigger.net

In this section, we'll look at how design issues and flawed handling of JSON web tokens (JWTs) can le......

In this section, we'll look at how design issues and flawed handling of JSON web tokens (JWTs) can leave websites vulnerable to a variety of high-severity attacks. As JWTs are most commonly used in authentication, session management, and access control mechanisms, these vulnerabilities can potentially compromise the entire website and its users.

Don't worry if you're not familiar with JWTs and how they work - we'll cover all of the relevant details as we go. We've also provided a number of deliberately vulnerable labs so that you can practice exploiting these vulnerabilities safely against realistic targets.

Labs

If you're already familiar with the basic concepts behind JWT attacks and just want to practice exploiting them on some realistic, deliberately vulnerable targets, you can access all of the labs in this topic from the link below.

Tip

From Burp Suite Professional 2022.5.1, Burp Scanner can automatically detect a number of vulnerabilities in JWT mechanisms on your behalf. For more information, see the related issue definitions on the Target > Issued definitions tab.

What are JWTs?

JSON web tokens (JWTs) are a standardized format for sending cryptographically signed JSON data between systems. They can theoretically contain any kind of data, but are most commonly used to send information ("claims") about users as part of authentication, session handling, and access control mechanisms.

Unlike with classic session tokens, all of the data that a server needs is stored client-side within the JWT itself. This makes JWTs a popular choice for highly distributed websites where users need to interact seamlessly with multiple back-end servers.

JWT format

A JWT consists of 3 parts: a header, a payload, and a signature. These are each separated by a dot, as shown in the following example:

eyJraWQiOiI5MTM2ZGRiMy1jYjBhLTRhMTktYTA3ZS1lYWRmNWE0NGM4YjUiLCJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJwb3J0c3dpZ2dlciIsImV4cCI6MTY0ODAzNzE2NCwibmFtZSI6IkNhcmxvcyBNb250b3lhIiwic3ViIjoiY2FybG9zIiwicm9sZSI6ImJsb2dfYXV0aG9yIiwiZW1haWwiOiJjYXJsb3NAY2FybG9zLW1vbnRveWEubmV0IiwiaWF0IjoxNTE2MjM5MDIyfQ.SYZBPIBg2CRjXAJ8vCER0LA_ENjII1JakvNQoP-Hw6GG1zfl4JyngsZReIfqRvIAEi5L4HV0q7_9qGhQZvy9ZdxEJbwTxRs_6Lb-fZTDpW6lKYNdMyjw45_alSCZ1fypsMWz_2mTpQzil0lOtps5Ei_z7mM7M8gCwe_AGpI53JxduQOaB5HkT5gVrv9cKu9CsW5MS6ZbqYXpGyOG5ehoxqm8DL5tFYaW3lB50ELxi0KsuTKEbD0t5BCl0aCR2MBJWAbN-xeLwEenaqBiwPVvKixYleeDQiBEIylFdNNIMviKRgXiYuAvMziVPbwSgkZVHeEdF5MQP1Oe2Spac-6IfA

The header and payload parts of a JWT are just base64url-encoded JSON objects. The header contains metadata about the token itself, while the payload contains the actual "claims" about the user. For example, you can decode the payload from the token above to reveal the following claims:

{ "iss": "portswigger", "exp": 1648037164, "name": "Carlos Montoya", "sub": "carlos", "role": "blog_author", "email": "carlos@carlos-montoya.net", "iat": 1516239022 }

In most cases, this data can be easily read or modified by anyone with access to the token. Therefore, the security of any JWT-based mechanism is heavily reliant on the cryptographic signature.

JWT signature

The server that issues the token typically generates the signature by hashing the header and payload. In some cases, they also encrypt the resulting hash. Either way, this process involves a secret signing key. This mechanism provides a way for servers to verify that none of the data within the token has been tampered with since it was issued:

- As the signature is directly derived from the rest of the token, changing a single byte of the header or payload results in a mismatched signature.

- Without knowing the server's secret signing key, it shouldn't be possible to generate the correct signature for a given header or payload.

Tip

If you want to gain a better understanding of how JWTs are constructed, you can use the debugger on jwt.io to experiment with arbitrary tokens.

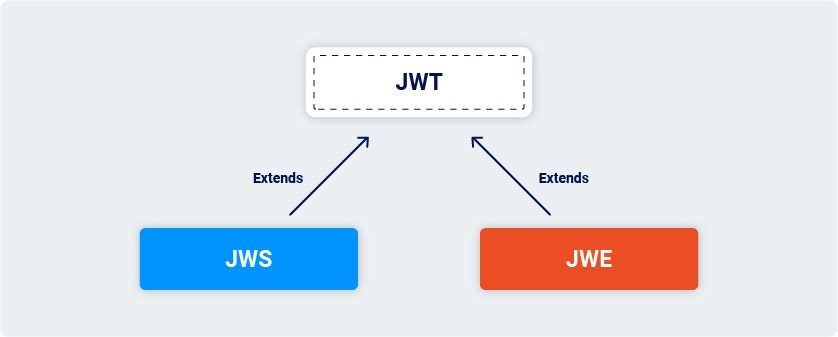

JWT vs JWS vs JWE

The JWT specification is actually very limited. It only defines a format for representing information ("claims") as a JSON object that can be transferred between two parties. In practice, JWTs aren't really used as a standalone entity. The JWT spec is extended by both the JSON Web Signature (JWS) and JSON Web Encryption (JWE) specifications, which define concrete ways of actually implementing JWTs.

In other words, a JWT is usually either a JWS or JWE token. When people use the term "JWT", they almost always mean a JWS token. JWEs are very similar, except that the actual contents of the token are encrypted rather than just encoded.

Note

For simplicity, throughout these materials, "JWT" refers primarily to JWS tokens, although some of the vulnerabilities described may also apply to JWE tokens.

What are JWT attacks?

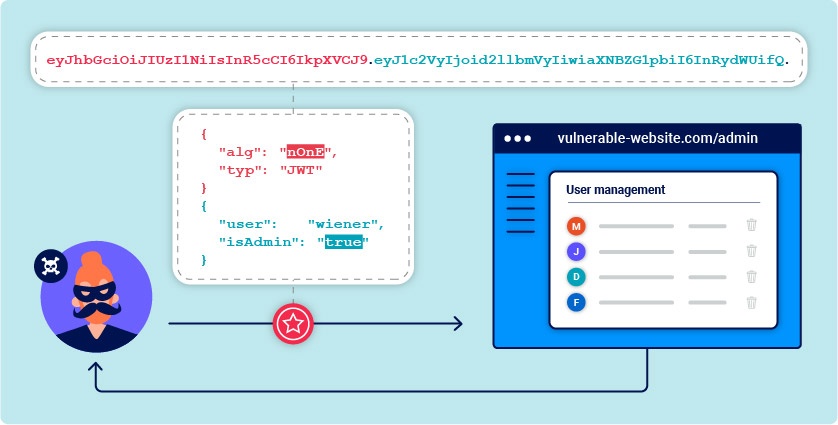

JWT attacks involve a user sending modified JWTs to the server in order to achieve a malicious goal. Typically, this goal is to bypass authentication and access controls by impersonating another user who has already been authenticated.

What is the impact of JWT attacks?

The impact of JWT attacks is usually severe. If an attacker is able to create their own valid tokens with arbitrary values, they may be able to escalate their own privileges or impersonate other users, taking full control of their accounts.

How do vulnerabilities to JWT attacks arise?

JWT vulnerabilities typically arise due to flawed JWT handling within the application itself. The various specifications related to JWTs are relatively flexible by design, allowing website developers to decide many implementation details for themselves. This can result in them accidentally introducing vulnerabilities even when using battle-hardened libraries.

These implementation flaws usually mean that the signature of the JWT is not verified properly. This enables an attacker to tamper with the values passed to the application via the token's payload. Even if the signature is robustly verified, whether it can truly be trusted relies heavily on the server's secret key remaining a secret. If this key is leaked in some way, or can be guessed or brute-forced, an attacker can generate a valid signature for any arbitrary token, compromising the entire mechanism.

How to work with JWTs in Burp Suite

In case you haven't worked with JWTs in the past, we recommend familiarizing yourself with the relevant features of Burp Suite before attempting the labs in this topic.

Exploiting flawed JWT signature verification

By design, servers don't usually store any information about the JWTs that they issue. Instead, each token is an entirely self-contained entity. This has several advantages, but also introduces a fundamental problem - the server doesn't actually know anything about the original contents of the token, or even what the original signature was. Therefore, if the server doesn't verify the signature properly, there's nothing to stop an attacker from making arbitrary changes to the rest of the token.

For example, consider a JWT containing the following claims:

{ "username": "carlos", "isAdmin": false }

If the server identifies the session based on this username, modifying its value might enable an attacker to impersonate other logged-in users. Similarly, if the isAdmin value is used for access control, this could provide a simple vector for privilege escalation.

In the first couple of labs, you'll see some examples of how these vulnerabilities might look in real-world applications.

Accepting arbitrary signatures

JWT libraries typically provide one method for verifying tokens and another that just decodes them. For example, the Node.js library jsonwebtoken has verify() and decode().

Occasionally, developers confuse these two methods and only pass incoming tokens to the decode() method. This effectively means that the application doesn't verify the signature at all.

Accepting tokens with no signature

Among other things, the JWT header contains an alg parameter. This tells the server which algorithm was used to sign the token and, therefore, which algorithm it needs to use when verifying the signature.

{ "alg": "HS256", "typ": "JWT" }

This is inherently flawed because the server has no option but to implicitly trust user-controllable input from the token which, at this point, hasn't been verified at all. In other words, an attacker can directly influence how the server checks whether the token is trustworthy.

JWTs can be signed using a range of different algorithms, but can also be left unsigned. In this case, the alg parameter is set to none, which indicates a so-called "unsecured JWT". Due to the obvious dangers of this, servers usually reject tokens with no signature. However, as this kind of filtering relies on string parsing, you can sometimes bypass these filters using classic obfuscation techniques, such as mixed capitalization and unexpected encodings.

Note

Even if the token is unsigned, the payload part must still be terminated with a trailing dot.

Brute-forcing secret keys

Some signing algorithms, such as HS256 (HMAC + SHA-256), use an arbitrary, standalone string as the secret key. Just like a password, it's crucial that this secret can't be easily guessed or brute-forced by an attacker. Otherwise, they may be able to create JWTs with any header and payload values they like, then use the key to re-sign the token with a valid signature.

When implementing JWT applications, developers sometimes make mistakes like forgetting to change default or placeholder secrets. They may even copy and paste code snippets they find online, then forget to change a hardcoded secret that's provided as an example. In this case, it can be trivial for an attacker to brute-force a server's secret using a wordlist of well-known secrets.

Brute-forcing secret keys using hashcat

We recommend using hashcat to brute-force secret keys. You can install hashcat manually, but it also comes pre-installed and ready to use on Kali Linux.

Note

If you're using the pre-built VirtualBox image for Kali rather than the bare metal installer version, this may not have enough memory allocated to run hashcat.

You just need a valid, signed JWT from the target server and a wordlist of well-known secrets. You can then run the following command, passing in the JWT and wordlist as arguments:

hashcat -a 0 -m 16500 <jwt> <wordlist>

Hashcat signs the header and payload from the JWT using each secret in the wordlist, then compares the resulting signature with the original one from the server. If any of the signatures match, hashcat outputs the identified secret in the following format, along with various other details:

<jwt>:<identified-secret>

Note

If you run the command more than once, you need to include the --show flag to output the results.

As hashcat runs locally on your machine and doesn't rely on sending requests to the server, this process is extremely quick, even when using a huge wordlist.

Once you have identified the secret key, you can use it to generate a valid signature for any JWT header and payload that you like. For details on how to re-sign a modified JWT in Burp Suite, see Signing JWTs.

If the server uses an extremely weak secret, it may even be possible to brute-force this character-by-character rather than using a wordlist.

According to the JWS specification, only the alg header parameter is mandatory. In practice, however, JWT headers (also known as JOSE headers) often contain several other parameters. The following ones are of particular interest to attackers.

jwk(JSON Web Key) - Provides an embedded JSON object representing the key.jku(JSON Web Key Set URL) - Provides a URL from which servers can fetch a set of keys containing the correct key.kid(Key ID) - Provides an ID that servers can use to identify the correct key in cases where there are multiple keys to choose from. Depending on the format of the key, this may have a matchingkidparameter.

As you can see, these user-controllable parameters each tell the recipient server which key to use when verifying the signature. In this section, you'll learn how to exploit these to inject modified JWTs signed using your own arbitrary key rather than the server's secret.

Injecting self-signed JWTs via the jwk parameter

The JSON Web Signature (JWS) specification describes an optional jwk header parameter, which servers can use to embed their public key directly within the token itself in JWK format.

JWK

A JWK (JSON Web Key) is a standardized format for representing keys as a JSON object.

You can see an example of this in the following JWT header:

{ "kid": "ed2Nf8sb-sD6ng0-scs5390g-fFD8sfxG", "typ": "JWT", "alg": "RS256", "jwk": { "kty": "RSA", "e": "AQAB", "kid": "ed2Nf8sb-sD6ng0-scs5390g-fFD8sfxG", "n": "yy1wpYmffgXBxhAUJzHHocCuJolwDqql75ZWuCQ_cb33K2vh9m" } }

Public and private keys

In case you're not familiar with the terms"public key"and"private key", we've covered this as part of our materials on algorithm confusion attacks. For more information, see Symmetric vs asymmetric algorithms.

Ideally, servers should only use a limited whitelist of public keys to verify JWT signatures. However, misconfigured servers sometimes use any key that's embedded in the jwk parameter.

You can exploit this behavior by signing a modified JWT using your own RSA private key, then embedding the matching public key in the jwk header.

Although you can manually add or modify the jwk parameter in Burp, the JWT Editor extension provides a useful feature to help you test for this vulnerability:

- With the extension loaded, in Burp's main tab bar, go to the JWT Editor Keys tab.

- Generate a new RSA key.

- Send a request containing a JWT to Burp Repeater.

- In the message editor, switch to the extension-generated JSON Web Token tab and modify the token's payload however you like.

- Click Attack, then select Embedded JWK. When prompted, select your newly generated RSA key.

- Send the request to test how the server responds.

You can also perform this attack manually by adding the jwk header yourself. However, you may also need to update the JWT's kid header parameter to match the kid of the embedded key. The extension's built-in attack takes care of this step for you.

Injecting self-signed JWTs via the jku parameter

Instead of embedding public keys directly using the jwk header parameter, some servers let you use the jku (JWK Set URL) header parameter to reference a JWK Set containing the key. When verifying the signature, the server fetches the relevant key from this URL.

JWK Set

A JWK Set is a JSON object containing an array of JWKs representing different keys. You can see an example of this below.

{ "keys": [ { "kty": "RSA", "e": "AQAB", "kid": "75d0ef47-af89-47a9-9061-7c02a610d5ab", "n": "o-yy1wpYmffgXBxhAUJzHHocCuJolwDqql75ZWuCQ_cb33K2vh9mk6GPM9gNN4Y_qTVX67WhsN3JvaFYw-fhvsWQ" }, { "kty": "RSA", "e": "AQAB", "kid": "d8fDFo-fS9-faS14a9-ASf99sa-7c1Ad5abA", "n": "fc3f-yy1wpYmffgXBxhAUJzHql79gNNQ_cb33HocCuJolwDqmk6GPM4Y_qTVX67WhsN3JvaFYw-dfg6DH-asAScw" } ] }

JWK Sets like this are sometimes exposed publicly via a standard endpoint, such as /.well-known/jwks.json.

More secure websites will only fetch keys from trusted domains, but you can sometimes take advantage of URL parsing discrepancies to bypass this kind of filtering. We covered some examples of these in our topic on SSRF.

Injecting self-signed JWTs via the kid parameter

Servers may use several cryptographic keys for signing different kinds of data, not just JWTs. For this reason, the header of a JWT may contain a kid (Key ID) parameter, which helps the server identify which key to use when verifying the signature.

Verification keys are often stored as a JWK Set. In this case, the server may simply look for the JWK with the same kid as the token. However, the JWS specification doesn't define a concrete structure for this ID - it's just an arbitrary string of the developer's choosing. For example, they might use the kid parameter to point to a particular entry in a database, or even the name of a file.

If this parameter is also vulnerable to directory traversal, an attacker could potentially force the server to use an arbitrary file from its filesystem as the verification key.

{ "kid": "../../path/to/file", "typ": "JWT", "alg": "HS256", "k": "asGsADas3421-dfh9DGN-AFDFDbasfd8-anfjkvc" }

This is especially dangerous if the server also supports JWTs signed using a symmetric algorithm. In this case, an attacker could potentially point the kid parameter to a predictable, static file, then sign the JWT using a secret that matches the contents of this file.

You could theoretically do this with any file, but one of the simplest methods is to use /dev/null, which is present on most Linux systems. As this is an empty file, reading it returns an empty string. Therefore, signing the token with a empty string will result in a valid signature.

Note

If you're using the JWT Editor extension, note that this doesn't let you sign tokens using an empty string. However, due to a bug in the extension, you can get around this by using a Base64-encoded null byte.

If the server stores its verification keys in a database, the kid header parameter is also a potential vector for SQL injection attacks.

The following header parameters may also be interesting for attackers:

cty(Content Type) - Sometimes used to declare a media type for the content in the JWT payload. This is usually omitted from the header, but the underlying parsing library may support it anyway. If you have found a way to bypass signature verification, you can try injecting actyheader to change the content type totext/xmlorapplication/x-java-serialized-object, which can potentially enable new vectors for XXE and deserialization attacks.x5c(X.509 Certificate Chain) - Sometimes used to pass the X.509 public key certificate or certificate chain of the key used to digitally sign the JWT. This header parameter can be used to inject self-signed certificates, similar to thejwkheader injection attacks discussed above. Due to the complexity of the X.509 format and its extensions, parsing these certificates can also introduce vulnerabilities. Details of these attacks are beyond the scope of these materials, but for more details, check out CVE-2017-2800 and CVE-2018-2633.

JWT algorithm confusion

Even if a server uses robust secrets that you are unable to brute-force, you may still be able to forge valid JWTs by signing the token using an algorithm that the developers haven't anticipated. This is known as an algorithm confusion attack.

How to prevent JWT attacks

You can protect your own websites against many of the attacks we've covered by taking the following high-level measures:

- Use an up-to-date library for handling JWTs and make sure your developers fully understand how it works, along with any security implications. Modern libraries make it more difficult for you to inadvertently implement them insecurely, but this isn't foolproof due to the inherent flexibility of the related specifications.

- Make sure that you perform robust signature verification on any JWTs that you receive, and account for edge-cases such as JWTs signed using unexpected algorithms.

- Enforce a strict whitelist of permitted hosts for the

jkuheader. - Make sure that you're not vulnerable to path traversal or SQL injection via the

kidheader parameter.

Additional best practice for JWT handling

Although not strictly necessary to avoid introducing vulnerabilities, we recommend adhering to the following best practice when using JWTs in your applications:

- Always set an expiration date for any tokens that you issue.

- Avoid sending tokens in URL parameters where possible.

- Include the

aud(audience) claim (or similar) to specify the intended recipient of the token. This prevents it from being used on different websites. - Enable the issuing server to revoke tokens (on logout, for example).